A few weeks ago, I read “The Egg of a Sea-bird” on

’s substack, and got really interested in the work of Milman Parry and his assistant and successor Albert Lord.We’ll dig into the details, but broadly, Parry realized that the Homeric epics (both The Illiad and The Odyssey) were highly formulaic: they tended to use the same clusters or words, maybe adapted to the situation, a lot. And these tended to fit the constraint of the dactylic hexameter, the meter of Ancient Greek Poetry. From there, he realized that this property of Homer probably came from oral composition (as in composing the poem orally, in performance, as opposed to through writing), and went to study one of the last living oral epic tradition in Yugoslavia with his student and then assistant Albert Lord.

Now, I’m even less an expert on this topic than on what I usually write about. I can’t even read either of the languages, Ancient Greek and Serbo-Croatian, in which are composed the oral poems forming the basic data set for this research direction. So there is no way I’m going to fully do justice to the texts themselves, or come up with any new insight about them.

Yet even such my cursory understanding revealed a treasure of methodological insights, and that is something I’m fit to discuss in details.

Broadly, the Parry-Lord theory of composition offers me a way to explore three key methodological ideas:

How phenomenological compressions (summarizing the various patterns in the data) tends to precede mechanistic modelling (explaining how the system works), despite the modern mistake to equate “theory” with the latter.

How the mechanistic model of oral composition corresponds with the independently developed methods of the computer science field of procedural generation, and yet has sufficiently different goals to bring about some significant differences

A rich picture of the layers of epistemic regularities at play in most successful human endeavors (both for the oral singers and for the reconstruction of oral composition by analogy and textual analysis)

The Parry-Lord Story

Milman Parry, while an undergraduate in the 1920s, became obsessed with the highly formulaic aspect of Homer, and started a detailed and statistical study of these formulas, pushing the idea much further than anyone else before him. This eventually lead him to defend a brilliant PhD thesis in Paris, defending by this kind of textual analysis that Homer was a traditional author, who used extensively, almost exclusively, a traditional stock of parametric formulas.

Parry began with one recurrent pattern common among the Homeric epics: A god or hero says something, to which another character—perhaps the old warrior Nestor, or the goddess Athena, or Achilles—replies. That reply (rendered here in a romanized version of the Greek) typically reads Ton d’emeibet epeita…, “Then X replied to him….” But “X” was often not just Nestor, Athena, or Achilles, his or her name hanging limply alone. Rather, it would be, say, hippota Nestor, the chariot-fighter Nestor; or thea glaukopis Athene, the gray-eyed goddess Athena; or podarkes dios Achilleus, swift-footed godly Achilles. Twenty-seven different lines in the Iliad and the Odyssey, Parry found, conformed exactly to this pattern, many of them repeated numerous times. In each case, the epithet formula, in its metrical value, satisfied the hexametric line—whereas the name alone, or with a random adjective, would certainly not.

[…]

But this was only a foretaste of what Parry would take on over the next two hundred pages. For one thing, ancient Greek introduced complications through its case endings, changes in spelling, and pronunciation of a noun, including a name, such as Achilles, depending on its grammatical role in a sentence or line of verse. In English, the work of case is most often left to word order: Achilles stabbed the Trojan warrior. Or, The Trojan warrior stabbed Achilles. Thus, we have two sentences, with identical words and entirely different meanings, distinguished solely by their order in the sentence.Not so in Greek. Here, Achilles, in the “nominative” case, as the subject of the sentence, stabbing the Trojan, would have one case ending, and would sound one way—Achilleus. While the Achilles of the second sentence, in the “accusative” case, as direct object, stabbed by the Trojan soldier, would have a different case ending, Achillea, the syllabic sound pattern quite different.

There were three other cases (dative, genitive, and vocative), applying to both names and common nouns, that are basic to reading and understanding ancient Greek. But again, they don’t merely look different on the page. They often sound“different, typically with differing arrangements of “long” or “short” syllables.

In each instance, the epithets linked to these nouns, Parry showed, “responded” to the case differences, so as to make them fit the rhythm of the hexametric line; that is, the epithet accompanying a name in the nominative case typically differed from one used in, say, the accusative.

[…]

In the end, Parry all but proved that for each hero, god, or goddess, in each grammatical case, in each position in the hexametric line, there was normally only a single epithet that went with it. Achilles, in the genitive case, between the penthemimeral caesura and the end of the verse? That would be peleiadeo Achileos—“of Achilles, son of Peleus”—and nothing else.

(Robert Kanigel, Hearing Homer’s Song, 2021, p.106-108)

In Paris, both while he was writing his thesis and during this defence of it, Parry received feedback from Antoine Meillet, one of the professors advising him during his PhD in Paris on the aforementioned topic. Meillet drew out the many similarities between the formulaic style characterized by Parry, and the style of oral traditional poetry in Yugoslavia at the time.

My first studies were on the style of the Homeric poems and led me to understand that so highly formulaic a style could be only traditional. I failed, however, at the time to understand as fully as I should have that a style such as that of Homer must not only be traditional but also must be oral. It was largely due to the remarks of my teacher (M.) Antoine Meillet that I came to see, dimly at first, that a true understanding of the Homeric poems could only come with a full understanding of the nature of oral poetry. It happened that a week or so before I defended my theses for the doctorate at the Sorbonne, Professor Mathias Murko of the University of Prague delivered in Paris the series of conferences which later appeared as his book La Poésie populaire épique en Yougoslavie au début du XXe siècle. I had seen the poster for these lectures but at the time I saw in them no great meaning for myself. However, Professor Murko, doubtless due to some remark of (M.) Meillet, was present at my soutenance and at that time M. Meillet as a member of my jury pointed out with his usual ease and clarity this failing in my two books. It was the writings of Professor Murko more than those of any other which in the following years led me to the study of oral poetry in itself and to the heroic poems of the South Slavs.

(Milman Parry, Ćor Huso: A Study of Southslavic Song (1935) in The making of Homeric verse, 1987, p.439)

These similarities led Parry toward a new mechanistic model of how Homeric poetry was created, incorporating the demands and processes of oral composition.

For example, in his first published paper after his thesis, Parry already starts mentioning oral poetry as an underlying explanation for Homeric stylistic particularities (here enjambement, when a thought/sentence runs over the end of a poetic line into the next one):

Moreover Homer was ever pushed on to use unperiodic enjambement. Oral verse making by its speed must be chiefly carried on in an adding style. The Singer has not time for the nice balances and contrasts of unhurried thought: he must order his words in such a way that they leave him much freedom to end the sentence or draw it out as the story and the needs of the verse demand.

(Milman Parry, The Distinctive Character of Enjambement in Homeric Verse (1929) in The making of Homeric verse, 1987, p.253,256)

At some point in the early thirties, Parry decided that he couldn’t honestly trust his model of oral composition and defend it without having actually observed a breathing oral tradition. Which led him to learn Serbo-Croatian and to go to then-Yugoslavia to record oral songs. In the latter trip, he took with him one of his students at Harvard, Albert Lord.

Parry, through 2 long trips, recorded a wealth of songs, often both the actual performance and the dictated text, and conducted experiments that clarify many aspects of the process of oral composition.

Unfortunately, Parry dies just after coming back to Harvard, without having the time to make something of his massive experimental data.1

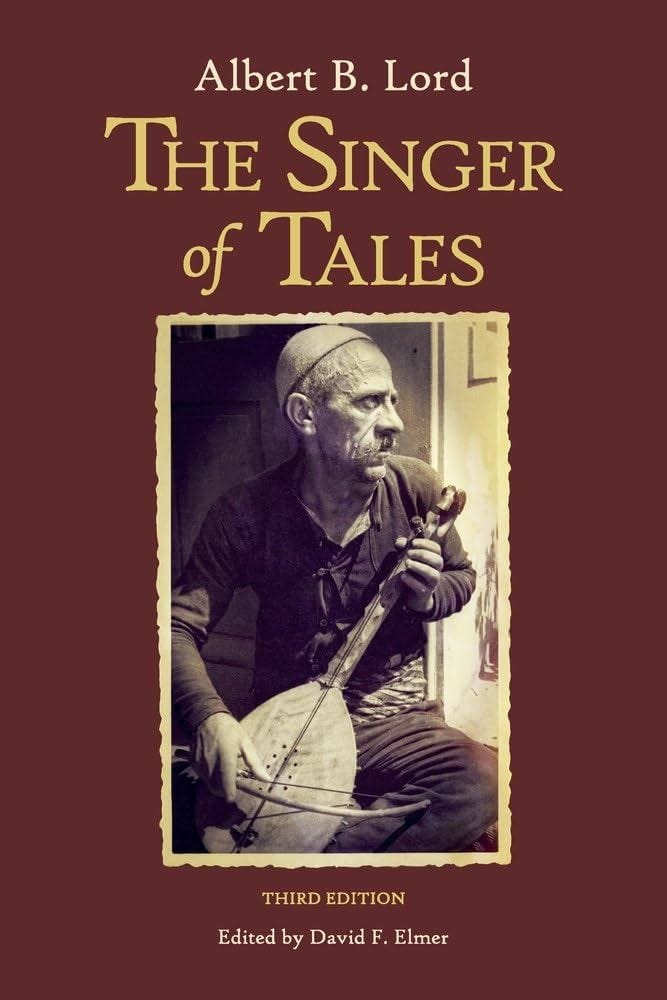

His assistant Lord, after a needed sabbatical from academia, then spent his whole career exploiting this wealth of data and bringing the theory of oral composition to fruition, culminating in his “The Singer of Tales”, which is the definitive modern exposition of the theory (known as Parry-Lord or oral-formulaic composition theory), and still considered a reference.

People who want more details on the history can go read the blog post mentioned above, and Kanigel’s biography of Parry, Hearing Homer’s Song.2

First, Phenomenological Compression

The first methodological point that come to my attention in this story is how Parry didn’t start with the whole mechanistic model of oral composition.

He didn’t even think of it as oral poetry initially, only as traditional. This is visible for example in his PhD thesis:

To establish in the Iliad and the Odyssey the existence of an artificial language is to prove that Homeric style, in so far as it makes use of elements of this language, is traditional. For the character of this language reveals that it is a work beyond the powers of a single man, or even of a single generation of poets ; consequently we know that we are in the presence of a stylistic element which is the product of a tradition and which every bard of Homer’s time must have used.

(Milman Parry, The Traditional Epithet in Homer, 1928, translated in The making of Homeric verse, 1987, p.6)

Instead, Parry started by noticing and characterizing detailed patterns within the lines of the Homeric epics (both the Illiad and the Odyssey).

The biggest/most prevalent such pattern was the concept of formulas. Parry defines them as:

a group of words which is regularly employed under the same metrical conditions to express a given essential idea.

(Milman Parry, Studies in the epic technique of verse making I: Homer and homeric style, 1930)

To really get it, it’s important to understand the constraint emerging from the main Ancient Greek meter, the dactylic hexameter. It provides a necessary pattern of feet made of fixed sequences of short and long syllables (quantity in that sense is a feature of Ancient Greek absent from English) that must be followed. It gives its recognizable rhythm to the epic poetry of Ancient Greece, notably the Homeric epics.

In addition, there are various positions in the line (inside the feet) where the break between words can be placed for particular emphasis. This is called the caesura, and follows a complex set of rules that I don’t truly get, but the details are not necessary to understand Parry’s insight.

The key point is that there are different ways to “split” the dactylic hexameter into pieces of known size and known rhythm, and this is where formulas come into action: they are recurrent patterns to express a given idea (say that a character is starting to talk) in a way that fits the metrical constraints of the next piece of line.

The Greek hexameter allows for greater variety, because the line may be broken at more than one place by a caesura. […] The caesura can occur in any one of the following points in the line: (a) after the first syllable of the third foot, (b) after the second syllable of the third foot if it is a dactyl, and (c) after the first syllable of the fourth foot. To these should be added (d) the bucolic diaeresis (after the fourth foot) and (e) the pause after a run-over word at the beginning of the line, which occurs most frequently after the first syllable of the second foot. One can, therefore, expect to find formulas of one foot and a half, two feet and a half, two feet and three quarters, three feet and a half, four feet, and six feet in length measured from the beginning of the line, and complementary lengths measured from the pause to the end of the line.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.152)

The simplest formulas are ones which can be reused as is; they tend to serve recurrent situations with no contextual elements.

First, there are those which have no close likeness to any other, as, so far as we know, is the case for ὀνείαθ᾽ ἑτοῖμα προκείμενα in the following verse, which is found three times in the Iliad and eleven times in the Odyssey:

οἱ δ᾽ ἐπ᾽ ὀνείαθ᾽ ἑτοῖμα προκείμενα χεῖρας ἴαλλον.

[they put their hands to the food that was prepared and ready.]

(Milman Parry, Studies in the epic technique of verse making I: Homer and homeric style, 1930)

But the most interesting formulas are those making what Parry calls a system: a set of formulas that have the same shape and general idea, but different specific words (for example, varying the names of characters as long as they fit the rhythm)

What’s essential about these formulas is that they are used in a highly “thrifty” way in Homer: there is next to no case where completely distinct formulas are used when one suffices.

It is the system of formulas, as we shall see, which is the only true means by which we can come to see just how the Singer made his verse; but we are interested in it now solely as a means of measuring the schematization of a poet’s style. There are in such a measuring two factors, that of length and that of thrift. The length of a system consists very obviously of the number of formulas which make it up. The thrift of a system lies in the degree in which it is free of phrases, which, having the same metrical value and expressing the same idea, could replace one another. What the length and thrift of a system of formulas are can best be explained by describing one of the most striking cases in Homer, that of a system of noun-epithet formulas for gods and heroes in the nominative. All the chief characters of the of the Iliad and the Odyssey, if their names can be fitted into the last half of the verse along with an epithet, have a noun-epithet formula in the nominative, beginning with a simple consonant, which fills the verse between the trochaic caesura of the third foot and the verse end: for instance, πολύτλας δῖος Ὀδυσσεύς [polútlas dĩos Odusseús - godlike much-enduring Odysseus]. It is the number of different formulas of this type, well above fifty, which makes the length of this system. But besides that there are, in only a very few cases, more than one such formula for a single character, though many of them are used very often, as πολύτλας δῖος Ὀδυσσεύς [polutlas dios Odusseus - godlike much-enduring Odysseus], which is found 38 times, θεὰ γλαυκῶπις Ἀθήνη [thea glaukopis Athene - gray-eyed Athena] 50 times, Ποσειδάων ἐνοσίχθων [Poseidaon enosikhthon - earth-shaker Poseidon] 23 times. To be exact, in a list of 37 characters who have formulas of this type, which includes all those having any importance in the poems, there are only three names which have a second formula which could replace the first.

(Milman Parry, Studies in the epic technique of verse making I: Homer and homeric style, 1930)

Notably, what is so different from the kind of poetry that we are used to, even Ancient Greek poetry after Homer, is the absence of focus on choosing the right and original word to fit the precise context: the epithet is the same whatever the situation.

Conceive Homer as an author from our own world and time, one who chooses words for their special effect at this or that moment in the story, and it would be easy to see the epithets as arbitrary or inept. But Parry was not interested in our world and time; to use his own word, he sought to “reconstitute” an earlier one. Audiences in earlier times didn’t read or hear the epithets as we do. For them, the epithets were all but permanently attached to the nouns they graced—rosy-fingered dawn, godlike Apollo. They appeared with them not when the story decreed but when they were needed to make the poem sound like a poem and not an unmelodic heap of words. Forget about the literary artist grasping for le mot juste; imagine, instead, the traditional bardic world’s common currency of sound and meaning laid at a poet’s feet, the formulaic epithets used as needed to move the great poem along.

(Robert Kanigel, Hearing Homer’s Song, 2021, p.108 )

Parry found other patterns in Homeric epics. For example, the shape of enjambement: the continuation of a thought and a syntactic proposition pass the end of a line, as opposed to finishing the clause at the end of the line.

As I mentioned in my post on English meter, enjambement is usually yielded as a way to produce specific effects, putting additional attention on the first word of the next line (and the potential surprise/unexpected nature of it)

What Parry showed is that the vast majority of enjambment in Homer were what he called “unperiodic”, or what subsequent scholars have called “additive”: although the sentence is not completed by the end of a line, the current thought has been fully completed, and the next part of the sentence only adds to it.

Broadly there are three ways in which the sense at the end of one verse can stand to that at the beginning of another. First, the verse end can fall at the end of a sentence and the new verse begin a new sentence. In this case there is no enjambement. Second, the verse can end with a word group in such a way that the sentence, at the verse end, already gives a complete thought, although it goes on in the next verse, adding free ideas by new word groups. To this type of enjambement we may apply Denis’ term unperiodic. Third, the verse end can fall at the end of a word group where there is not yet a whole thought, or it can fall in the middle of a word group; in both of these cases enjambement is necessary.

[…]

Thus we have found that Homer more often brings his thought to a close at the end of the verse than do later writers of the epic, and that he marks more strongly the rhythm of the hexameter.

(Milman Parry, The Distinctive Character of Enjambement in Homeric Verse (1929) in the making of Homeric verse, 1987, p.253,256)

And there are more subtle patterns, suggesting a generally “adding” style, where ideas and lines are accreted on top of each other, rather than having highly complex entanglement.

The singing of narrative in verses of equal length with a pause between each verse necessarily makes for an adding or, as it is usually called, an unperiodic style. The poet, thinking of his story verse by verse, wili only to a small extent be led to look further ahead than the verse end, and as a result, unless the sentence is to be limited in its length to the verse, that part of the sentence which comes after the first verse will be of such a kind that while it carries on and develops the thought of the first verse of the sentence, it is nevertheless not particularly indispensable to that first verse. This may be stated simply by saying that in narrative song the narrative can be broken off at almost any point and brought to a close with a period.

(Milman Parry, Ćor Huso: A Study of Southslavic Song (1935) in The making of Homeric verse, 1987, p.462)

These insights are not predictions from a specific model of oral composition (which Parry didn’t have in his early work), but rather the revelation of patterns present all along in the Homeric texts: phenomenological compressions of these texts. This corresponds to the “summarization” compression move that I described in a previous post.3

Once such phenomenological compressions exists, there is a grounding for building mechanistic models of the system. We now have patterns to explain and rederive, that is a standard with which to evaluate potential mechanistic/reductionist models.

This is a really important point about methodology in general, which tends to be completely missed by people lacking knowledge of history of science (or of history of any deep field).

Because we live in an age where incredibly powerful mechanistic models abound (notably in physics, but not only), modern people think of “correct theories/models/explanations” as first and foremost about these mechanistic models.

This is not wrong, in the sense that mechanistic models generalize much better; but it is missing the fact that it’s nigh impossible (and basically unheard of historically) to pull a working mechanistic model out of one’s ass without finding first phenomenological compressions and principles to anchor the search for mechanistic explanations.

So phenomenological compressions offer (mostly) stable targets for explanation by reduction, that is by lower-level mechanistic models. As such, they tend to precede mechanistic modeling.

Mechanics of Song (Re)generation

Now, let’s turn to the mechanistic model of oral composition unearthed by Parry and Lord on the basis of the Yugoslav recordings, transcriptions, and experiments.

What the experiments and recording in the living oral tradition of Yugoslav epic poetry gave Parry and Lord is both a much larger data set from which to extract phenomenological compressions, and also the direct observation (and some amount of intervention on) the process of oral composition. Lord then applied this mechanistic model back to Homer, showing convincingly that he was an oral poet.

The most straightforward description of the oral composition process is that a singer (almost always male) sits down at some coffee house or other communal space to sing a song that he knows, while playing the gusle, a one-string lute with a bow.

Epic poetry in Yugoslavia is sung on a variety of occasions. It forms, at the present time, or until very recently, the chief entertainment of the adult male population in the villages and small towns. In the country villages, where the houses are often widely separated, a gathering may be held at one of the houses during a period of leisure from the work in the fields. Men from all the families assemble and one of their number may sing epic songs.

[…]

What is true of the home gathering in the country village holds as well for the more compact villages and for towns, where the men gather in the coffee house (kafana) or in the tavern rather than in a private home.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.14)

Yet this is very different from singing or reciting a written poem, because there is no fixed text: the singer regenerates the text of the song from a skeleton of key events/plot points at every performance.

An oral poem is not composed for but in performance.

[…]

We must grasp fully who, or more correctly what, our performer is. We must eliminate from the word “performer” any notion that he is one who merely reproduces what someone else or even he himself has composed. Our oral poet is composer. Our singer of tales is a composer of tales. Singer, performer, composer, and poet are one under different aspects but at the same time. Singing, performing, composing are facets of the same act.

[…]

The singer begins to tell his tale. If he is fortunate, he may find it possible to sing until he is tired without interruption from the audience. After a rest he will continue, if his audience still wishes. This may last until he finishes the song, and if his listeners are propitious and his mood heightened by their interest, he may lengthen his tale, savoring each descriptive passage. It is more likely that, instead of having this ideal occasion the singer will realize shortly after beginning that his audience is not receptive, and hence he will shorten his song so that it may be finished within the limit of time for which he feels the audience may be counted on. Or, if he misjudges, he may simply never finish the song.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.13,16-17)

Every performance is a regeneration from scratch. Which means that they can, and do, differ wildly in terms of number of lines and content of the lines, even though the main story is mostly the same.

When the singer of tales, equipped with a store of formulas and themes and a technique of composition, takes his place before an audience and tells his story, he follows the plan which he has learned along with the other elements of his profession. Whereas the singer thinks of his song in terms of a flexible plan of themes, some of which are essential and some of which are not, we think of it as a given text which undergoes change from one singing to another. We are more aware of change than the singer is, because we have a concept of the fixity of a performance or of its recording on wire or tape or plastic or in writing. We think of change in content and in wording; for, to us, at some moment both wording and content have been established. To the singer the song, which cannot be changed (since to change it would, in his mind, be to tell an untrue story or to falsify history), is the essence of the story itself. His idea of stability, to which he is deeply devoted, does not include the wording, which to him has never been fixed, nor the unessential parts of the story. He builds his performance, or song in our sense, on the stable skeleton of narrative, which is the song in his sense.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.105)

This creates a hard problem for the singer: they have to come up lines of poetry that fit both the story that needs to be told, and the meter of the specific poetry, in real time.

In the Yugoslav poetry, the meter is the the Junacki Deseterac, a decasyllable meter with a fixed caesura after the fourth syllable.

From then on what he does must be within the limits of the rhythmic pattern. In the Yugoslav tradition, this rhythmic pattern in its simplest statement is a line of ten syllables with a break after the fourth. The line is repeated over and over again, with some melodic variation, and some variation in the spacing and timing of the ten syllables.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.22)

And the singer has to be impressively fast.

If we are fully aware that the singer is composing as he sings, the most striking element in the performance itself is the speed with which he proceeds. It is not unusual for a Yugoslav bard to sing at the rate of from ten to twenty ten-syllable lines a minute. Since, as we shall see, he has not memorized his song, we must conclude either that he is a phenomenal virtuoso or that he has a special technique of composition outside our own field of experience. We must rule out the first of these alternatives because there are too many singers; so many geniuses simply cannot appear in a single generation or continue to appear inexorably from one age to another. The answer of course lies in the second alternative, namely, a special technique of composition.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.17)

In practice, what Parry and Lord found was that singers solved this problem by learning and internalizing methods to quickly generate:

lines with the correct meter (formulas)

concrete instantiations of the right story beats (themes)

poetic and descriptive details (ornaments)

We have already seen what formulas look like in the Homeric epics; now such formulas are explained by their usefulness.4

The formulas represented by the preceding examples are the foundation stone of the oral style. We have seen them from the point of view of the young singer with an essential idea to express under different metrical conditions. Their usefulness can be illustrated by indicating the many words that can be substituted for the key word in such formulas.

[…]New formulas are made by putting new words into the old patterns. If they do not fit they cannot be used, but the patterns are many and their complexity is great, so that there are few new words that cannot be poured into them.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.36,45)

In other words, the manner of learning described earlier leads the singer to make and remake phrases, the same phrases, over and over again whenever he needs them. The formulas in oral narrative style are not limited to a comparatively few epic "tags," but are in reality all pervasive. There is nothing in the poem that is not formulaic.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.49)

Or, to alter the image, we find a special grammar within the grammar of the language, necessitated by the versification. The formulas are the phrases and clauses and sentences of this specialized poetic grammar. The speaker of this language, once he has mastered it, does not move any more mechanically within it than we do in ordinary speech.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.37)

Second, but also essential, are themes. These are a new phenomenological compression that Lord extracted from the much more extant corpus of Yugoslav songs. He found that an individual singer usually learned some way to instantiate a common situation (say an assembly), and used this when singing his songs, including when learning new songs from others.

The theme, even though it be verbal, is not any fixed set of words, but a grouping of ideas.

[…]

A major theme, then, can take several possible forms in a singer's repertory. When he hears such a theme in a new song, he tends to reproduce it according {81|82} to the material already in his possession. Minor themes also have a number of forms suitable to several different situations. Such a minor theme, indispensable to narrative, is that of writing a letter.

[…]

Usually the singer invites the same heroes in each song in which this theme is used. He does not learn a special set of names for each song. When he finds it necessary to gather an army or wedding guests, he has the theme ready in his mind.

[…]

The order is different, but the personnel is the same. The theme is always at hand when the singer needs it; it relieves his mind of much remembering, and leaves him free to think of the plan of the song itself or of the moment of the song in which he is involved.

[…]

A singer ordinarily has one basic form for such a minor theme; it is flexible and within limits adaptable to special circumstances. But when such circumstances are absent, the singer makes no attempt to alter its general pattern

[…]

From the time that maturity is reached and the singer has established the general outlines of a theme, evidence seems to indicate that he changes it little if at all.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.72,86,91,99)

Parry and Lord even managed to study the learning of a new song from one singer to another, and found that the learner used his own themes to regenerate the song.

When Parry was working with the most talented Yugoslav singer in our experience, Avdo Međedović in Bijelo Polje, he tried the following experiment. Avdo had been singing and dictating for several weeks; he had shown his worth and was aware that we valued him highly. Another singer came to us, Mumin Vlahovljak from Plevlje. He seemed to be a good singer, and he had in his repertory a song that Parry discovered was not known to Avdo; Avdo said he had never heard it before. Without telling Avdo that he would be asked to sing the song himself when Mumin had finished it, Parry set Mumin to singing, but he made sure that Avdo was in the room and listening. When the song came to an end, Avdo was asked his opinion of it and whether he could now sing it himself. He replied that it was a good song and that Mumin had sung it well, but that he thought that he might sing it better. The song was a long one of several thousand lines. Avdo began and as he sang, the song lengthened, the ornamentation and richness accumulated, and the human touches of character, touches that distinguished Avdo from other singers, imparted a depth of feeling that had been missing in Mumin's version.

[…]

The main points of Mumin's account of the assembly are there, but by elaboration, by the addition of similes and of telling characterization, Avdo has not only lengthened the theme from 176 lines to 558, but he has put on it the stamp of his own understanding of the heroic mind. Yet Mumin's performance was not Avdo's only model for this passage. Avdo had other models as well, already in his mind as he listened to Mumin. These models were the assembly theme that he sang in his own repertory. Avdo had worked these out during his many years of singing.

[…]

It is to be noted that Avdo differed from Mumin in the description of the arrival of the messenger in the assembly. Mumin simply said that the door creaked and a messenger entered. Avdo described how Mustajbey looked out the window and saw a cloud of dust from which emerged a rider bearing a message on a branch. From a consideration of the arrival scenes in the tale of Osman, one can see that Avdo has used his own firmly entrenched method of describing arrivals.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.82-83,85)

Last but not least, an essential skill for a brilliant singer is to be able to “ornament”, that is to extend and give more depth of feeling and sensation to a certain scene, mandated either by some intuition of its importance, or by the opportunity to sing for longer, or some other reason.

These, Parry and Lord realized, often follow some learned order, and work in the “additive” manner described by Parry for Homer, allowing the singer to pile as many details as he wants before moving forward.

The varying degrees of elaboration of the theme of arming used by Homer are similar to those of the Yugoslav singers, extending from the single line to longer passages.

[…]

In building a large theme the poet has a plan of it in his mind beyond the bare necessities of narrative. There are elements of order and balance within themes. The description of an assembly, for example, follows a pattern proceeding from the head of the assembly and his immediate retinue through a descending hierarchy of nobles to the cupbearer, who is the youngest in the assembly and hence waits upon his elders, but ending with the main hero of the story. This progression aids the singer by giving him a definite method of presentation. A similar plan can be seen in the gathering of an army. Here the order is often an ascending one. And almost invariably the last hero to be invited and the last to arrive is Tale of Orašac, a man of great individuality. Sometimes the singer merely adds one name after another as they occur to him until he has exhausted his store and then he caps the list with Tale.

[…]

In all these instances one sees also that the singer always has the end of the theme in his mind. He knows where he is going. As in the adding of one line to another, so in the adding of one element in a theme to another, the singer can stop and fondly dwell upon any single item without losing a sense of the whole. The style allows comfortably for digression or for enrichment. Once embarked upon a theme, the singer can proceed at his own pace. Wherever possible he moves in balances: from boots to cap, from a sword on the left side to powder box on the right. Moreover, he usually signals the end of a theme by a significant or culminating point. The description of an assembly moves inexorably to focus on the chief hero of the song; the description of a journey moves toward its destination; headdress and armor are the most glorious accoutrements of a warrior; the larger assembly theme proceeds onward to the decision which will itself lead to further action. The singer's mind is orderly.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.87-88)

In addition to this mechanistic model of oral composition, Lord even offers a developmental model of how singers learn to compose orally. All these generators come from listening to older singers, internalizing heard formulas, themes, ornamentations, as well as the more subtle points like which themes go together in the tradition, and even patterns about where word breaks tend to fall within the line.

If the singer has no idea of the fixity of the form of a song, and yet has to pour his ideas into a more or less rigid rhythmic pattern in rapid composition, what does he do? To phrase the question a little differently, how does the oral poet meet the need of the requirements of rapid composition without the aid of writing and without memorizing a fixed form? His tradition comes to the rescue. Other singers have met the same need, and over many generations there have been developed many phrases which express in the several rhythmic patterns the ideas most common in the poetry. These are the formulas of which Parry wrote. In this second stage in his apprenticeship the young singer must learn enough of these formulas to sing a song. He learns them by repeated use of them in singing, by repeatedly facing the need to express the idea in song and by repeatedly satisfying that need, until the resulting formula which he has heard from others becomes a part of his poetic thought. He must have enough of these formulas to facilitate composition. He is like a child learning words, or anyone learning a language without a school method; except that the language here being learned is the special language of poetry.

[…]

The singer never stops in the process of accumulating, recombining, and remodeling formulas and themes, thus perfecting his singing and enriching his art. He proceeds in two directions: he moves toward refining what he already knows and toward learning new songs. The latter process has now become for him one of learning proper names and of knowing what themes make up the new song. The story is all that he needs; so in this stage he can hear a song once and repeat it immediately afterwards—not word for word, of course—but he can tell the same story again in his own words.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.22,26)

And since no one learn form exactly the same singers, in the same configuration, the stock of themes, formulas, and all around patterns of any singer is different from those of the others.

Although the formulas which any singer has in his repertory could be found in the repertories of other singers, it would be a mistake to conclude that all the formulas in the tradition are known to all the singers. There is no "check-list" or "handbook" of formulas that all singers follow. Formulas are, after all, the means of expressing the themes of the poetry, and, therefore, a singer's stock of formulas will be directly proportionate to the number of different themes which he knows. Obviously singers vary in the size of their repertory of thematic material; the younger singer knows fewer themes than the older; the less experienced and less skilled singer knows fewer than the more expert. Even if, individually, every formula that a singer uses can be found elsewhere in the tradition, no two singers would at any time have the same formulas in their repertories. In fact, any given singer's stock of formulas will not remain constant but will fluctuate with his repertory of thematic material. Were it possible to obtain at some moment of time a complete repertory of two singers, no matter how close their relationship, and from that repertory to make a list of the formulas which they know at that moment of time, there would not be complete identity in the two lists.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.50-51)

There are even more subtle points in this mechanistic model.

Say how parts of a song get more or less fixed in shape depending on how often the song is sung; because at this point the singer will have sung the song closely enough that he can remember some of his lines or ways of implementing themes, and this is easier than regenerating them, leading to them getting more and more fixed.

Or how singers learn more than just themes and formulas, but also deep underlying complexes of themes: what kind of event goes with each other, and how they tend to relate to each other.

These complexes are held together internally both by the logic of the narrative and by the consequent force of habitual association. Logic and {96|97} habit are strong forces, particularly when fortified by a balancing of elements in recognizable patterns such as those which we have just outlined. Habitual association of themes, however, need not be merely linear, that is to say, theme b always follows theme a, and theme с always follows theme b. Sometimes the presence of theme a in a song calls forth the presence of theme b somewhere in the song, but not necessarily in an а-b relationship, not necessarily following one another immediately. Where the association is linear, it is close to the logic of the narrative, and the themes are generally of a kind that are included in a larger complex. I hesitate to call them "minor" or "nonessential" or "subsidiary," because sometimes essential ideas may be expressed in them. Where the association is not linear, it seems to me that we are dealing with a force or "tension" that might be termed "submerged." The habit is hidden, but felt. It arises from the depths of the tradition through the workings of the traditional processes to inevitable expression.

[…]

In our investigation of composition by theme this hidden tension of essences must be taken into consideration. We are apparently dealing here with a strong force that keeps certain themes together. It is deeply imbedded in the tradition; the singer probably imbibes it intuitively at a very early stage in his career. It pervades his material and the tradition. He avoids violating the group of themes by omitting any of its members.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.102-104)

Or what this model implies for notions of “consistency” and “unity” in epic poems.

We have exercised our imaginations and ingenuity in finding a kind of unity, individuality, and originality in the Homeric poems that are irrelevant. Had Homer been interested in Aristotelian ideas of unity, he would not have been Homer, nor would he have composed the Iliad or Odyssey. An oral poet spins out a tale; he likes to ornament, if he has the ability to do so, as Homer, of course, did. It is on the story itself, and even more on the grand scale of ornamentation, that we must concentrate, not on any alien concept of close-knit unity. The story is there and Homer tells it to the end. He tells it fully and with a leisurely tempo, ever willing to linger and to tell another story that comes to his mind. And if the stories are apt, it is not because of a preconceived idea of structural unity which the singer is self-consciously and laboriously working out, but because at the moment when they occur to the poet in the telling of his tale he is so filled with his subject that the natural processes of association have brought to his mind a relevant tale. If the incidental tale or ornament be, by any chance, irrelevant to the main story or to the poem as a whole, this is no great matter; for the ornament has a value of its own, and this value is understood and appreciated by the poet's audience.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.158)

But let’s move forward to a deep similarity between this model of oral composition and a modern field of computer science, procedural generation (proc gen).

Procedural Generation And Oral Composition

Procedural generation mostly comes from a time before the modern AI revolution, before LLMs and image generation let people just ask for something with text. Then, the only known ways to automatically generate artefacts with desirable properties (images, video game levels, music…) was through explicit procedural methods: combining prebuilt pieces in various ways (using combinators, or grammars, or mutations), throw in some randomness to ensure variation and diversity(footnote about pseudo randomness), and get something out, hopefully with the right properties.5

A classic example in video games is the roguelike Spelunky. In it, you play a series of 2d levels which are generated anew for each run.

As this delightful website shows, Spelunky levels are generated by randomly sampling a path from starting point to finish along a 2d grid, where each cell corresponds to a “room”.

Each room (both along the path and outside of it) is selected from a set of possible rooms with the right properties (notably having exits in the right place if on the path), and then additional randomness decides the fine details of each room (if there is gold, or enemies…).

This is surprisingly similar to the Parry-Lord mechanistic model of oral composition: singers have learned generators, both at the level of the lines (formulas), but also at the level of the general story (themes), which they then use to regenerate a song from the remembered high-level story beats.

We can even make sense about some of the difficulties and subtleties of oral composition through the theoretical analysis of proc gen.

Notably, the key feature of generation in oral composition is the lack of take-backs: one cannot change what the previous lines and story beats — only addition and moving forward is possible.

In the language of proc gen, this means that backtracking is forbidden. Backtracking is a feature of some generation methods where if, at any point, it becomes clear that there is no way of finishing the generation while ensuring the desired property, the method is allowed to “backtrack”, that is to roll back some of the previous choices and try another path.

This is exactly what singers cannot do. So they have to rely on generation without backtracking. Which creates a host of difficulties well-known in proc gen.

For example, without backtracking, you need to avoid potential dead-ends, where you risk not being able to finish the generation in a consistent manner.

The splitting of lines of poetry into pieces on both side of the caesura, and the learning of formulas for each side, help a lot with that. So does the adding style, from enjambement to ornamentation.

I would also expect, though neither Parry nor Lord discuss it, that the lack of backtracking might be a force behind the absence of end rhyme in basically all known oral traditions: end-rhyme risks backing you into a corner by forcing you to find the right word to finish the follow-up line.

Now, there’s another no-backtracking issue with rhyming, especially elaborate rhyming schemes: they increase the demands on memory.

For without backtracking, you also need to remember enough of your previous decisions to not contradict yourself, or lose yourself.

This is a really hard thing to do when writing a procedural generator without backtracking, and is made even harder in oral composition because the singer has almost no time to think about the constraints imposed by his past decisions — he must go on at speed.

So the tradition helps singers limit how much they need to remember: though they might interrupt a theme by another theme, say a story within a story or the reception of a letter, they rarely go beyond a few levels deep, and avoid highly complex laced structure as is common in more modern poetry and stories.

Even then, there are times where the singer, either because of some pull from his generators, or from forgetting some past decision, ends up making the song inconsistent.

One of the most glaring inconsistencies of this sort within my experience of Yugoslav oral song occurs in Đemail Zogić's song of the rescue of Alibey's children by Bojičić Alija (I, No, 24). The young hero has neither a horse nor armor with which to undertake his mission, and his mother borrows them from his uncle, Rustembey. Later in the poem there is a recognition scene in which Alija is recognized because he is wearing the armor of Mandušić Vuk, whom he overcame in single combat. Zogić has not made {94|95} the necessary adjustment in the theme of recognition so that it would agree with the theme of the poor hero who borrows his armor. This theme of recognition we know was not in the version which Zogić learned from Makić. Zogić has used another form of the theme of recognition, and it was not right for the particular song. Yet seventeen years later when Zogić sang the same song it contained the same inconsistency. We know the cause of it. It is more difficult to understand its persistence.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.100)

The learner usually employs his own form of any given theme rather than the form that he has heard from the other singer. Sometimes the singer who is learning has to restrain himself from doing this, that is, from following his own theme rather than another's. If he did not take care, he would fall into self-contradiction later. Avdo is trapped in this way briefly, and not very significantly, at the beginning of theme 5 (see Appendix I). According to his habit, when a letter is delivered, the recipient opens it and reads it and the head of the assembly asks about the letter. This Avdo causes to happen in our story, forgetting that the messenger is waiting for a reward; momentarily Avdo is carried on by habit and for a few lines neglects the theme of paying the messenger, a really important theme in this song, a distinctive part of it. Later Avdo has to repeat the theme of reading the letter, thus causing a minor inconsistency.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.109)

It’s really exciting to see two quite different fields independently come up with similar methods to tackle similar problems. This points to features and regularities of “generation under resource constraints” that are particularly suited to this type of procedural generation methods.

And yet, the two methods do differ, because their respective end goals also differ.

Different Goals, Subtly Different Methods

One of the main themes Lord emphasizes repeatedly throughout “The Singer of Tales” is that singers in the Yugoslav tradition, and by analogy any oral poet, do not aim for originality or personal expression.6

In order to avoid any misunderstanding, we must hasten to assert that in speaking of "creating" phrases in performance we do not intend to convey the idea that the singer seeks originality or fineness of expression. He seeks expression of the idea under stress of performance. Expression is his business, not originality, which, indeed, is a concept quite foreign to him and one that he would avoid, if he understood it. To say that the opportunity for originality and for finding the "poetically" fine phrase exists does not mean that the desire for originality also exists. There are periods and styles in which originality is not at a premium. If the singer knows a ready-made phrase and thinks of it, he uses it without hesitation, but he has, as we have seen, a method of making phrases when he either does not know one or cannot remember one. This is the situation more frequently than we tend to believe.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.46)

Yet neither do they they try to emulate exactly, word-for-word a pre-existing text. Indeed, without writing, since no singer can reliably repeat the exact same song, there is no stable feedback signal to learn a song by heart.

If the singer of oral epic always sang a song in exactly the same words, it would be possible, of course, to ask him to repeat the performance a number of times and thus to fill in on the second or third singing what was lost in notating the first singing. But bards never repeat a song exactly, as we have seen. This method, although it has been used often, never results in a text that truly represents any real performance. It produces a composite text even when a singer's song is fairly stable, as we know it may be with shorter epics. In a truly oral tradition of song there is no guarantee that even the apparently most stable "runs" will always be word-for-word the same in performance.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.134)

Actual performance is too rapid for a scribe. One might possibly suggest that the scribe might write as much as he could at one performance, correct it at the next, and so on until he had taken down the text of the whole from several singings. I mention this because Parry had an assistant in the field at the beginning who thought that he could do this, but the variations from one singing to another were so great that he very soon gave up trying to note them down.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.159)

And even when songs do get written down, as long as the singer inhabits the oral tradition, he will not care about the exact wording, nor treat the written text as a fixed standard

Even when the text was read to him from a book—and I should like to emphasize this—Avdo made no attempt to memorize a fixed text. He did not consider the text in the book as anything more than the performance of another singer; there was nothing sacred in it. One may assume that by this time he had already worked out the theme of the assembly and had it well established in his mind as Hivzo slowly spelled out Šemić's song.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.83)

This goal, of recreating a song that is fitting for the tradition, without having an observable standard to draw from, is quite different from the goals of procedural generation. Usually, proc gen emphasizes variety and interestingness: we want to create original and diverse artefacts, either purely for an artistic purpose, or to, say, provide replayable content in a video game.

From this discrepancy of goals emerges a discrepancy of methods.

Notably, proc gen relied fully on simulated randomness for its variety; whereas oral composition has no use for it.

The singers could, if they wanted, take some events happening during a performance and use them as a rough analog random number generators. But they have no interest in that: their goal is not variety or originality — it is to be able to adapt their knowledge and generators to the song at hand.

Similarly, while proc gen avoids repetition as much as possible, oral poetry is particularly thrifty: reusing the same formulas and themes and instantiation as often as possible, when it make sense. Still, it’s worth noting that what counts as the same context for a singer is actually quite subtle.

Our brief excursion into the principle of thrift in actual oral composition among Yugoslav singers has served to emphasize the context of the moment when a given line is made. In order to understand why one phrase was used and not another, we have had to note not only its meaning, length, and rhythmic content, but also its sounds, and the sound patterns formed by what precedes and follows it. We have had to examine also the habits of the singer in other lines, so that we may enter into his mind at the critical creative moment. We have found him doing more than merely juggling set phrases. Indeed, it is easy to see that he employs a set phrase because it is useful and answers his need, but it is not sacrosanct. What stability it has comes from its utility, not from a feeling on the part of the singer that it cannot or must not be changed. It, too, is capable of adjustment. In making his lines the singer is not bound by the formula. The formulaic technique was developed to serve him as a craftsman, not to enslave him.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.55)

So despite non-trivial convergence of methods, oral composition and procedural generation differ quite a lot due to their distinct goals. This is yet another illustration of how essential goals are for methodological analysis: the value of a method is always dependent on the chosen goal.

Intricate Patterns of Epistemic Regularities

Last but not least, I want to quickly mention the various epistemic regularities at hand in all of this. Reminder that by epistemic regularities, I mean the structural properties of the world that we can exploit to avoid doing all the intractable stuff.

As an example, one of the regularity of cooking is that it is tolerant to errors in measurement: if I get the weights of ingredients slightly off, this mostly changes nothing. Whereas patisserie lacks this: measurements must be precise, because variation risks changing which chemical reaction happens when, and destroying the structural integrity of the whole cake.

The first kind of regularity at stake here is the formulaic nature of oral poetry. Because it is so traditional and formulaic, it creates patterns that can be compressed, and then used to differentiate oral compositions from literate ones.

This is how Parry figured out in the first hand that Homeric epics were oral.

Here, not only is the regularity useful to separate oral vs literate poetry, but it is also so pervasive that it even reveals literate imitators of oral poetry.

There seem always to be signs in the songs themselves that point to the fact that they are written and not oral. In a fully developed written tradition of literature the formulas are no longer present. They are not needed. There may be repeated phrases, but the proportion of them to the whole is small. Words are chosen for nontraditional effects and placed in patterns which are not those of the tradition. Thus the basic patterns behind the formulas are changed. Lines are unique, and are intended as such. The meter is strictly regular. If there are "runs" (which ordinarily do not occur) they are used by the author for a special effect and do not arise simply from the habitual association in composition. This is again impossible because of the uniqueness of each line.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.142)

Then there are the regularities underlying the very oral composition.

A highly difficult problem, quick oral composition of complex poems with technical meters and complex stories, was turned into something feasible by the massively formulaic patterns used by singers

That is, the problem was redefined in order to create new regularities making the oral tradition feasible.7

Of course, I’m not claiming that any of the singers actively sought this methodological improvement; I expect it to have evolved organically, as the singers and their audience selected what worked best and emulated that.

Finally, there is what I call an access regularity hidden behind the Parry-Lord story.

Remember that the initial, and arguable final point was about Homer. What both Parry and Lord wanted to understand was how Homer composed his epics. Yet they had no way of observing the composition, nor any trace of it beside the poems themselves.

What helped them was the existence of an analogous oral tradition in Yugoslavia at the time; one they could go explore, and even experiment on a bit.

This strikes me as one of the regularities that Adrian Currie promotes in “Rock, Bone, and Ruin” as coming to the help of the historical sciences: analogies with existing systems, which let historical scientists experiment on their dead and buried topics, to some extent.

Of course, it’s important to keep in mind the differences between the two analogues, to explain discrepancies. For example, Lord considers how the two meters of Yugoslav and Homeric epics respectively differ, and what this means for the tradition.

In his study of enjambement in the Homeric poems Parry indicated that necessary enjambement is much less common in the epics of Homer than in Virgil or Apollonius. The line is a metrical unit in itself. In Yugoslav song necessary enjambement is practically nonexistent. The length of the hexameter is one of the important causes of the discrepancy between the two poetries. It is long enough to allow for the expression of a complete idea within its limits, and on occasion it is too long. Then a new idea is started before the end of the line. But since there is not enough space before the end to complete the idea it must be continued in the next line. This accounts for systems of formulas that have been evolved to fill the space from the bucolic diaeresis to the end of the line, with complementary systems to take care of the run-over words in the following line.

(Albert Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960 (original edition) - 2019 (third edition), p.155)

Conclusion

All in all, I have found a veritable wealth of methodological examples and insights in this line of research.

Thanks again to

for starting me on this topic with her substack. If you found the subject of oral composition and Homeric epic entrancing despite the ridiculous length of this post, I recommend reading her substack Homeric Questions!There is apparently a massive debate about Parry’s death, whether it was an accident (as officially claimed), a murder by his wife, or a suicide. I’m not that interested in the question, but curious conspiracy theorists can check Robert Kanigel’s biography of Milman Parry, Hearing Homer’s Song.

How crazy is it that the same author also wrote a biography of Ramanujan, of all people?

Note that the enjambement pattern lies on the cusp of Parry building a mechanistic model of oral composition, which he mentions in the paper itself. But it still fits my point, in that it is a phenomenological compression first and foremost, that he then tries to explain mechanistically.

I don’t go into this aspect of the theory, but it’s important to know that Lord argues repeatedly that formulas and themes are not just useful, but also probably coming from the ritual and religious origins of the tradition.

For those interested in an introduction, the best one I know is this tumblr post: So you want to build a generator…

This is one difference between say singers and jazz improvisers. The latter aim for personal expression in their solos. Another difference lies in the existence of a fixed starting point (the jazz standard) for the latter.

Wild speculation: maybe this had some causal impact on the emergence of caesura? Because a lot of the power of formulas rely on the existence of caesura, so they might have emerged partially to create nicer regularities.

Love this so much! I really enjoyed revisiting these works through your eyes. You have accumulated so much knowledge and insight into my field in just a few weeks time. Really

impressive !